But after that, they ask me another question: "Chad Handley, you witty, talented son of a bitch, just how in Creation did you come up with that cover?"

So, I thought I'd do this little blog post to explain how comic book covers come about. There's a slight problem with that agenda, as in general I have no idea how comic book covers come to be. Presumably, at the larger comic companies there's some kind of streamlined process the particulars of which I am wholly ignorant. I do, however, know the twisted, tortured, circuitous route by which penciler extraordinaire Fernando Brazuna and I came up with the cover for Theodicy #1. So, that's what I'm fixin' to learn you about, as we say around these parts.

After we talked via skype for about an hour swapping ideas, the first thing Fernando did was quickly sketch out several of our concepts, just so we could see them on paper:

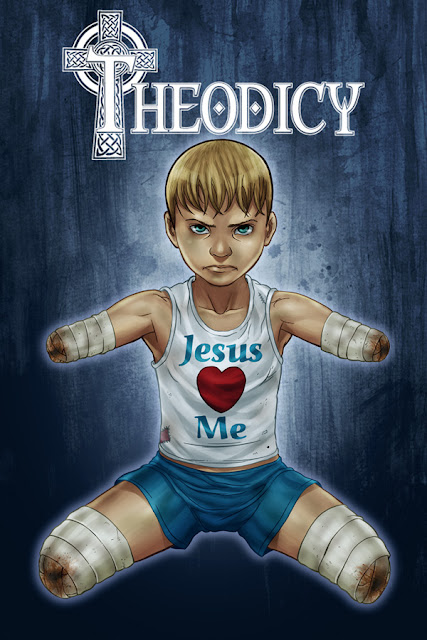

So, pretty early on, we had the idea for what ended up being the final cover. Though he doesn't remember this, the idea was originally Fernando's. He suggested we show Timothy, the child on the cover, wearing a shirt that says "I love Jesus." My brilliant contribution was to suggest that the shirt instead say "Jesus Loves Me," and nuggets of narrative wisdom like that are why I pay myself the big bucks.

As you can see, most of our cover ideas involved images of Timothy, although there were a couple of more traditional "team shot" concepts we were throwing around. In the end, we decided to go with the most attention-getting cover, which is basically sketch one. That cover also had the advantage of being the most thematically informative cover, as for me it spells out the entire agenda of the book in one image. "If Jesus loves this kid so much, why doesn't he have any limbs?" It's the problem of evil stated in a snap shot.

Once we had settled on sketch number one as a cover, Fernando sketched a layout. For the uninitiated (which was me a couple of months ago) a layout is just a rough sketch a penciler makes before he puts the finishing touches on an image. Here's Fernando's layout of the cover for issue 1:

Usually, the writer never sees the layout, but Fernando, God bless him, likes to show me layouts so that I can approve compositions before he completes the art. As you can see, at this stage the logo for the comic had not been finalized, so Fernando was sketching in a placeholder for the sake of composition.

Once I approved this basic composition, Fernando set to work. It takes Fernando about a day to draw a page of sequential art, which is the normal, expected professional rate. Even though the cover is only one image, it is the most important image of the book, so Fernando took a whole day to produce this, a beautiful, detailed pencil drawing of the cover:

Yeah, Fernando's pretty good. At this point we felt pretty good about Timothy, particularly his expression. But we weren't crazy about the font of the lettering on his shirt. We wanted it to be clearly visible across the room in a comic book shop. Fernando made a few passes at the letters, but couldn't get it right.

If you're new to comics, you might not know that the penciler, the guy who draws the comics, does not write the balloons. That's actually the job of this whole other guy, the letterer (in our case, the multi-talented and reproductively-fit John M. Burton). So, although Fernando found it easy to create this beautiful image of Timothy, it took him a while to produce a suitable font for his shirt. But, on the third try, he finally got it:

So, the next stage after one receives a final piece of penciled art is to hand things over to the inker. The inker, as his name suggests, carefully goes over pencil drawings in ink. This makes the image easier to color for the colorist and easier to print at the printers. At this point, we shipped the pencils off to master inker and occasional-email-returner Ryan Boltz, who worked his magic thusly:

See how much bolder and clearer the lines are now after Ryan has had his way with them? That's a big deal because, as you might know if you've ever had to photocopy something written in pencil, pencil drawings don't print very well. And although the work will be colored, the pencil work at the core will show better once a good inker has gone over the lines.

So, now the image gets shipped to the colorist. (By the way, I use the term "ship" metaphorically. Usually, I just send the images as an email attachment, or over dropbox. That's how a writer in North Carolina can have a penciler in Brazil, an inker in Virginia, a colorist in Indonesia, and a letterer in New York City. This book would have been impossible before skype and before paypal. I'm told in the old days, physical copies of the images had to be shipped around town via bike messenger. And in the REALLY old days, the ORIGINAL art had to be shipped around town via horse and buggy (or whatever people drove before there were photocopiers). Which is why you used to have to live in New York City to do monthly comics, but no more thanks to Al Gore's wonderful invention.)

My colorist, Minan Ghibliest, and I had a brief skype conversation on the direction of the covers, with some input from Fernando. Fernando preferred a more sparse coloring style, which he showed us via this quick mock-up:

Which Fernando and I thought was a bit too"firmamenty." We also thought it looked a bit too much like God was rapturing the kid, or at least looking down on him, which sort of defeated the purpose of the image.

So, Hegelian that I am, I made of Fernando's thesis and Minan's antithesis a synthesis, and suggested that they split the difference. There should be something in the background, but it should be more visual noise than heavenly light. So, from that, Minan produced this:

The final version of the cover. I should add that the logo was designed by all-around comics genius Cary Kelley, who you might now as the writer of Dynagirl, but who also happens to be a very talented designer of logos, as you can see.

And that's how it all went down. Interestingly enough, now that I'm sending the book out and receiving scant editorial attention, it seems that most publishers prefer the "team shot" image of all the major characters heroically posing and staring as a cover for a first issue. It helps the reader understand whose story the book will tell better than an image like ours, which only states the thematic agenda of the story. I've gotten a few suggestions to somehow add Paul and Father John, the main characters of the book, to the cover. So far, I've resisted this suggestion, but if I ever change my mind, I'll do another blog post and show you how that process.

So, that's how comic book covers are made. Next week: laws and sausages.